Dheeraj Jayant

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are at the forefront of the planetary crises of climate change and biodiversity loss. Due to their geography, small size, isolation, and limited natural resources, SIDS face amplified vulnerabilities. Rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns threaten their economies, societies, and very existence. These challenges directly impact all sectors of SIDS economies—from agriculture and fisheries to tourism—and therefore have cascading effects on food security, livelihoods, and cultural traditions.

Cabo Verde provides a striking example of these vulnerabilities. While each of its islands has its own character and ecological challenges, in this blog we will focus on providing resources on Brava, the smallest inhabited island of the archipelago, where our work is focused.

The Climate Context of Cabo Verde: Cabo Verde’s climate is characterized by aridity, highly variable rainfall, and long dry seasons. Although Cabo Verde has contributed 0.00% historical responsibility for climate change, data shows that the country has been paying the price since at least the mid-20th century:

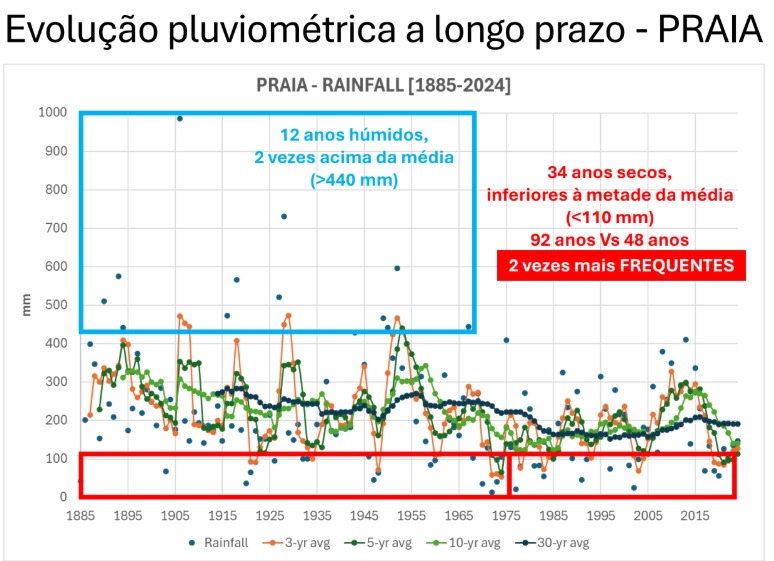

Historical pluviometric data from 1885 to 2024 shows a stark divide*:

- 1885–1955: rainfall patterns were more balanced, with droughts occurring, but at longer intervals.

- 1955–present: droughts have become twice as frequent and markedly more severe.

Source: Ozer et Thibault: Socio-Anthropological Analysis of Migration Movements and Forms of Resilience of the Cape Verdean Population in the Face of Climate Change and Drought Risk

*Note: In this case, we used Ozer and Thibault’s data from Praia – Santiago, since data is deficient for Brava.

Since 2017, Cabo Verde has been experiencing yet another prolonged drought—what can perhaps be described as the ‘new normal’. At the same time, the islands are not spared from the opposite extreme: flash floods that can devastate infrastructure, agriculture, and fragile ecosystems within hours. In addition to the devastating impact of water scarcity and floods, landslides and seismic activity further increase the islands’ vulnerability.

This climate instability leaves both human and non-human communities—whose fates are increasingly interlinked in the context of such a highly modified ecosystem—struggling to adapt. Although the impacts of this climate profile are felt across both urban and rural Cabo Verde, the rural population disproportionately bears the brunt of extreme weather events.

Today, agriculture contributes only about 8% of Cabo Verde’s GDP, yet around a third of the population lives in rural communities that depend directly or indirectly on agriculture. Almost 45% of the rural population is classified as living in poverty by national standards. In just the last two decades, around 85,000 rural Cape Verdeans have emigrated either to urban areas or abroad.

The forces driving this emigration are multi-factorial—historical, cultural, economic and social—but it is undeniable that the exposure to climate risk is an important factor influencing this rural exodus. The weight of emigration is felt at all levels of society and has been expressed by Cape Verdean artists and poets. Our own small team has experienced the emigration of 6 permanent staff and interns in the span of 18 months.

The Biodiversity Context of Cabo Verde: Despite its arid climate, landscape transformations, and long history of ecological change, Cabo Verde harbors a remarkable variety of terrestrial and marine biodiversity, much of it found nowhere else on Earth.

Terrestrial Biodiversity: Cabo Verde’s terrestrial ecosystems, though relatively small in scale, are home to emblematic and unique species:

- Flora and vegetation: including the Cape Verdean Dragon Tree (Dracaena caboverdeana), the Ironwood Tree (Sideroxylon marginatum), the Cape Verdean Date Palm (Phoenix atlantica), and over 92 endemic plant species adapted to the unique conditions of the archipelago.

- Reptiles: Cabo Verde is a hotspot for reptiles, with several endemic geckos and skinks.

- Birds: the islands host both resident and migratory bird populations, including rare endemics such as the Garça vermelha (Ardea purpurea bournei) and the Cagarra (Calonectris edwardsii).

- Insects: though less studied, insects are key pollinators and part of the food chain that sustains reptiles and birds.

Cabo Verde’s endemic flora has survived waves of ecological transformation—from the expansion of sugarcane and cotton monocultures to the widespread adoption of low-diversity rainfed agriculture (corn, beans, and squash). Local rural communities may have played a vital role in this survival, drawing on traditional ecological knowledge to use and conserve plant species for ornamental, medicinal, and cultural purposes.

Marine Biodiversity: The surrounding Atlantic waters are equally unique. Specific ecological conditions—the narrow shelf belt, the reduced intertidal zone, the seasonality of marine biological productivity, and scarce precipitation—result in a low density of marine organisms but an exceptionally fragile and diverse ecosystem. These unique conditions provide a habitat of considerable endemism:

- Fish: more than 20 endemic fish species, along with unique cryptobenthic species and crabs.

- Marine turtles: the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta), for which Cabo Verde is the third most important nesting site worldwide.

- Marine mammals: dolphins are frequent visitors, and humpback whales migrate here to reproduce.

- Sharks and rays: 14 species of sharks from six families—including tiger sharks, blacktip sharks, and lemon sharks—alongside rays such as the round fantail stingray and mobula ray.

- Invertebrates: cone snails and other mollusks add to the uniqueness of marine ecosystems.

Source: Marine Biodiversity around Cape Verde

Threats: This fragile biodiversity faces increasing threats, many of which are directly linked to the socio-ecological pressures described earlier.

For terrestrial conservation, the primary threats are:

- Land-use change and uncontrolled free grazing

- Climate change and desertification

- Loss of traditional ecological knowledge and practices

- Invasive species competing with or displacing native species

Many of the terrestrial threats are inextricably linked to the rural exodus: the abandonment of cultivation increases free grazing, weakens social controls and regimes over land use, and reduces the availability of labor for ecological restoration.

For the marine ecosystem, the primary threats include:

- Unsustainable fishing practices, especially intensive semi-industrial and industrial fishing*

- Marine habitat degradation

*Note: Brava does not have any semi-industrial or industrial boats. However, its waters experience semi-industrial fishing from boats from other islands.

Digging Deeper: Root Causes and Paths Forward

The conservation challenges in Cabo Verde are not simply ecological—they are deeply historical, sociological, and political. These challenges often reflect historical injustices affecting both human and non-human communities. Efforts to reverse long-term environmental degradation must avoid superficial or simplistic interpretations of current resource regimes (often labeled as “irrational,” “wasteful,” “overexploited,” or “mismanaged”). If environmental action does not engage with the historical roots of these problems, we risk addressing only the symptoms rather than the underlying causes. Using a field-based metaphor (inspired by our invasive species management project), this could end up merely pruning the problems—unintentionally reinforcing them—rather than eradicating them.

A political-ecology perspective reveals how colonial agriculture, structural poverty, and migration have contributed to current socio-ecological crises. Understanding these deep-rooted causes provides valuable insights for designing pragmatic conservation strategies that balance biodiversity protection with the realities of rural livelihoods and development needs.

Read more in Part 2: Digging Deeper: Tracing the Roots of Cabo Verde’s Socio-Ecological Crises