‘For what may we hope? What can we know? What ought we do?’

In the context of rural exodus, unemployment, water scarcity, environmental degradation and limited access to essential services like transportation and healthcare, what possible strategies can be developed and mobilized to prioritize the restoration of ecosystems and conservation of endangered endemic biodiversity and in Small Island Developing States? At Biflores, we reflect constantly on this question to define our interventions and adapt our strategy.

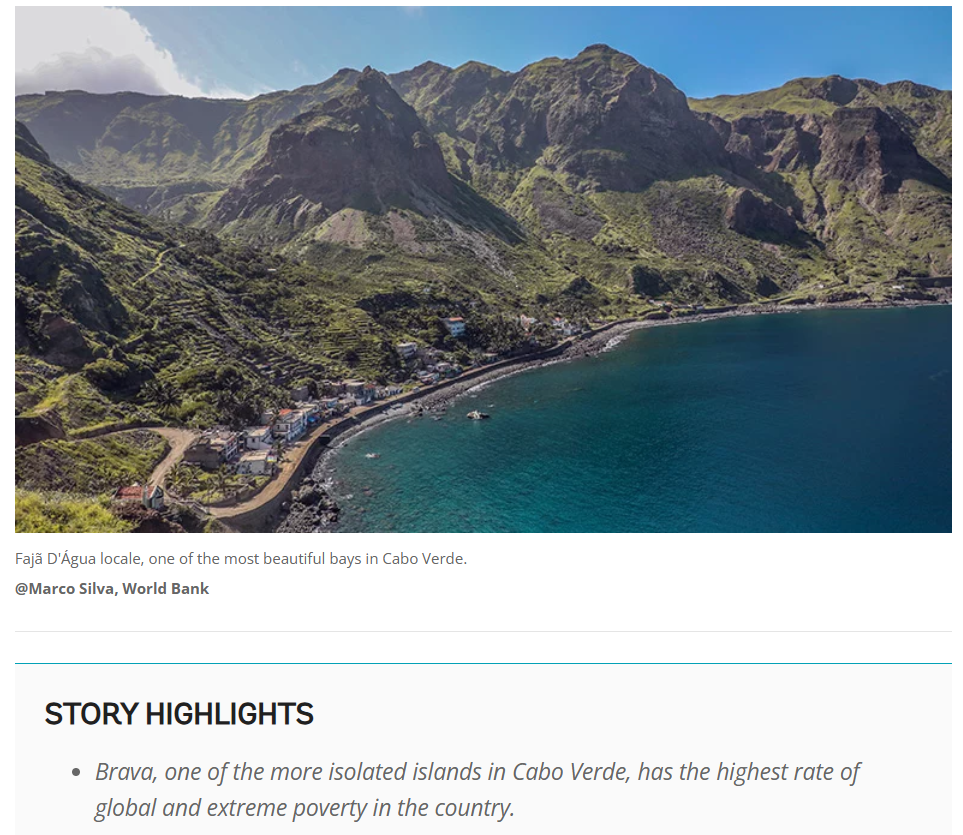

Brava’s integrated human and non-human societies have shown formidable resilience in the face of historic socio-ecological challenges. Despite the almost total modification of the ecosystems, many endemic species of terrestrial and marine flora and fauna have survived. Despite regular droughts, flashfloods, tremors, landslides, and the difficulty of access to the island, local communities take pride in their culture of farming, cattle rearing and fishing.

Migration is integrated into Brava’s DNA. From the late 18th century, Brava’s skilled fishermen and sailors were recruited by American whalers from New Bedford, who passed by Cabo Verde to restock on supplies. By the mid-19th century, vibrant communities of ‘Bravenses’ (many working in the fishing, agriculture and maritime industries) were established in the Northeast of the United States, especially in New Bedford and Pawtucket. The early post-Independence years saw a significant increase of migration, especially by privileged landowners/colonial administrators, who feared land-seizure for redistribution by the socialist government. This historic migration has brought about a Transatlantic existence, with people always having “one foot in each country”. However, especially over the last three decades, social, economic and climatic forces have begun to devastate the island’s human resources. Since the 50 years of Cape Verdean independence, despite significant public investments in the electrification of the island and improved access to water for domestic use, Brava has lost 50% of its population. Bravenses from all socio-economic backgrounds seek economic opportunity, reunite with family, and pursue simple curiosity about the country that so profoundly shapes the economy of the island. The interconnected dynamics of poverty, education, criminal justice, and immigration policy in the United States reverberate and shape lives both in Brava and within the diaspora communities.

The rapid change in the social ecosystem of the island has impacted every aspect of life: from music and culture to the spread of invasive species and increased free grazing. A recent diagnostic study on Brava, organized by the municipality of Oeiras, highlighted some of the main challenges for human development on the island. These include:

- Water scarcity

- Isolation and transport

- Healthcare access

- Education, training and unemployment

Given these realities of life on Brava, in 2023 we at Biflores decided to dedicate a significant amount of our time and resources to developing a strategic plan based on a pragmatic methodology of socially and environmentally just conservation. Confident in our ethic that conservation and restoration efforts must engage people who interact with local ecosystems, and integrate livelihoods needs with conservation, we sought to answer the questions:

- What are the means by which biodiversity conservation can maximize the potential of rural development? What approaches might permit an increased role of local communities in conservation and democratic governance of natural resources?

- How do local communities and institutions imagine simultaneously increasing food insecurity, improving human well-being and tackling biodiversity loss?

- Under the current institutional regime, which strategies might be most effective to empower local communities to reverse the trends of biodiversity loss?

To answer these questions, we used the limited formally available information and began to re-discover the island through intensive field work: training on conservation of endemic species, followed by botanical surveys, ecological hikes and institutional visits to gather information. Perhaps more importantly, we organized informal knowledge gathering through long conversations and interactions within our society: with cattle breeders, with farmers, with fishermen and with repositories of traditional ecological knowledge. The finer strokes of the realist portrait of contemporary Brava are revealed via these informal interactions – football games, cards, cups of ‘grogu’, fishing expeditions, overnight camping on the beaches. Reconnecting with the landscapes, observing and documenting the various components of biodiversity, listening intently from rural community members, elders, youth and music provided us with precious tools to better understand the dynamics of the ecosystems and how society interacts with them.

After a good year of intense conversations, hikes, community parties, football games, debates and reflection and implementation of pilot projects on endemic flora protection and marine ecosystem data collection, we possessed an augmented understanding of our island, the challenges faced by human and non-human communities, and various ideas from local stakeholders on how to deal with them. We bore witness to the first hand evidence of the resilience of farmers, cattle breeders, and the cultural importance of the agriculture and livestock sector. This provided us with the first elements to respond to our questions:

- Biodiversity conservation has significant potential to strengthen rural development when it builds on the resilience, ingenuity, and cultural traditions of local communities. Farmers and cattle breeders are not only the backbone of local food production but also potential key custodians of landscapes and biodiversity. One powerful example lies in pastoralism. Beyond its economic and cultural role, pastoralism, if oriented with the right resources, could contribute to positive externalities including landscape maintenance, biodiversity management, and even the control and utilization of introduced species that have turned invasive. By aligning conservation efforts with the value of these practices, it is possible to design approaches that provide dual benefits for nature and people. Likewise, the creativity of local farmers—such as their ingenious condensation of cloud-moisture in the highlands to sustain agriculture and cattle breeding—shows how traditional adaptation strategies can inform future-looking resilience models. Increasing the role of local communities in conservation depends on creating participatory governance structures. Farmers, herders, and artisans must be empowered not as beneficiaries, but as decision-makers and partners. This requires recognizing their knowledge, ensuring fair participation, and linking biodiversity goals to tangible community benefits such as better pastures, reduced losses from invasive species, and new artisanal value chains. By elevating local voices, conservation becomes a shared responsibility grounded in lived realities

- For Brava’s rural communities, food security, human well-being, and biodiversity protection are not competing goals. They can well be intertwined, if the right resources and orientation are provided. Adaptation practices (like cloud-moisture harvesting and agroecology) could both boost yields and restore ecological functions, showing how ecological stewardship can directly enhance well-being.

- Within today’s institutional landscape, empowering local communities to reverse biodiversity loss requires a mix of recognition, investment, and policy support. Recognizing community-conserved areas provides legitimacy to local stewardship. Building capacity for value-addition—whether through sustainable livestock management, innovative uses of invasive species and agroecology—creates new opportunities for people and nature. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern science broadens the toolkit for conservation. And supportive policy frameworks that reward sustainable practices ensure that communities are not penalized for using ‘nature’

Biflores’ methodology to support local visions of development and conservation is based on designing programs around livelihood resilience and ecological restoration that can foster a virtuous cycle where food security and biodiversity reinforce each other.

Given our geographic isolation, a reliable network of national and international partners is essential to advancing our work. We rely on the scientific community for technical support that strengthens our ability to understand the dynamics of endemic species. We depend on partner organizations for organizational support that helps us build a solid association, with strong governance, financial transparency, and strategic vision. We count on the institutional backing of the democratically elected bodies of Brava and Cabo Verde, and on the financial commitment of partners who believe in our mission. From these partnerships we learn what we aspire to do—and just as importantly, what we wish to avoid. Above all, we value partnerships of equals, grounded in respect and trust for local visions of the future.

With a foundation based on a solid understanding of our human and non-human communities, a methodology of holistic, adaptive management, a strong network of support and successfully implemented pilot projects, we now have a supply of perhaps our most important resource: radical hope. In the face of increasing uncertainties, hope allows us to remain unwaveringly committed to the possibility of a better future for our communities and the unique species that have evolved on Brava.